My trigger to write on this topic started a few years ago when I was an active participant in the demonstrations in the west bank, Palestine, against the separation wall. My camera was damaged by a tear gas canister that was thrown at me by the Israeli army forces. It was not only the camera that was neutralized, I also felt the strong effect of this action upon me. It caused me to think about the role of the camera as an object, the camera itself, and the possible reasons why it was a concrete object of target and a mean of violence as stones and tear gas were. I was curious to explore the presumptions and power the camera imposes by its presence. Namely, the event of taking photos- “photo-shooting” itself.

In this paper, I depicted elements from Henry Lefebvre’s Right to the city(1968) as a conceptual structure of creation of social space together with Ariella Azouly’s Civil contract of photography(2008), where she seeks to analyze photography within the framework of citizenship as a status, an institution, and a set of practices (page 22). I will focus only on the elements of space and plurality while examining scenes from the film “5 Broken cameras”, 2011 (Davidi/Burnat) and interviews with the directors illustrating Bili’n’s documented struggle as a permissive right.

The Palestinian village of Bil’in is located in the central West Bank, twelve kilometers west of Ramallaha. Bil’in is a small agricultural village which faces several illegal Jewish settlements such a “Matetiau” and “Modein Ilit”. These settlements are populated almost exclusively by orthodox Jews and are extending every year. The separation wall which was built by the Israeli government starting 2003, was intended to protect the new settlements from their Palestinian neighbors. Normally, a fence is placed surrounding the area one wants to protect, in this case, it was planned in a way of encircling Bil’in, confiscating half of the their agriculture areas. The inhabitants of the village demonstrated against the wall every Friday after prayer for several years.

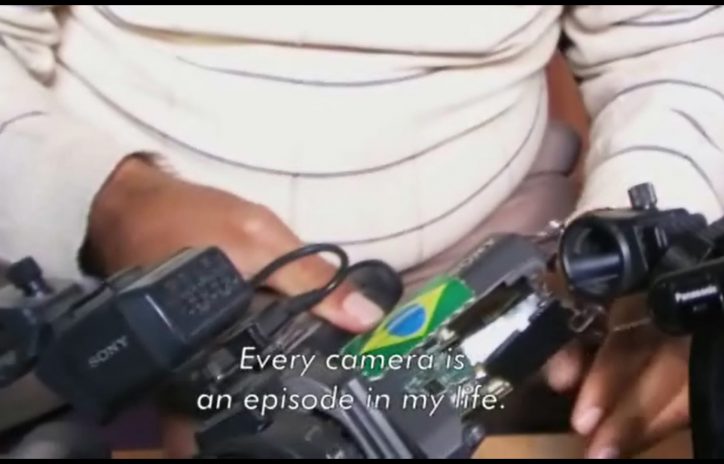

The film was shot almost entirely by a Palestinian farmer Emad Burnat, who bought his camera in 2005 to record the birth of his youngest son. Burnat shot 700 hours of footage. In 2009 Israeli co-director and an activist, Guy Davidi joined the project and together they scripted and edited the film centered on the recurring destruction of 5 of Burnat’s cameras. As a first general input we can see that one of the great qualities of the film’s storyline is the ongoing shift between the shots that were taken in the private household, the intimate space of everyday life and the public struggle which is another aspect of everyday life in the village. The camera is present in both situations and became the third hand of the director. In one of the interviews with the co-directors Davidi was asked about Burnat and replied:

“He was very important. Because he was a villager who had a camera. There were hundreds of journalists from all over the world. There was even a big film made around that time. But Burnat was the only one who stayed there during the week, after the demonstrators left. So, when soldiers came during the night or made arrests, he was the only one to film that, his camera was always present “.

Lefebvre, while using the concept of the production of space, posits a theory that understands space as fundamentally bound to social reality. It follows that space “in itself” can never serve as an epistemological starting position. Space does not exist “in itself”; it is produced. The Production of urban space is where the state-dominant force is a joint force, a force which in order to dominate society, necessarily imposes the control of the production of space. In other words, this spaticalization in contemporary cities and urban locality is alienated from its users because it is produced for them by others. We are left with an abstract space, a reduced space that simplifies the complexity of property and territory and diminishes the multi-layer decision making regarding the space to a flat unity. We can understand the alienation of everyday life of the Palestinians under occupation as an abstract space as well. It is composed of different distributions of resources, of different legal rights and freedom of movement, or of a physically separated interference such as the separation wall. In the political-economical context of the middle east, when the state and its military governing apparatus violate or deny the very basic rights of a social collective, the right to space production is a right to necessity. Lefebvre claims that inhabitants must re-appropriate the abstract urban space through a process of political mobilization that struggles for grassroots control on the decision- making and allows the space to be managed in a new setup.

In this context, the film exposes the conflicting system of representations within the abstract space – between the dominant urban ideology and the camera as a representation apparatus. The camera participates in the abstract space, and by its ability to capture and contain it, also interrupts and appropriates it. Through the camera we are either introduced to a new space or, rather, to a new assertion of one. Nevertheless, it raises distinctions and triggers us to redefine and re-think of the cameras position.

The films tells us that in the same time when there is a physical resistance, struggle, and violence, there is also communication and a dialog. An encounter in which the presents of the camera reviles. Ariela Azouly defines it as “The space of plurality” she writes: The camera produces an image of the occurrence, rather than an invention of an individual. In the moment of the shooting, the singular disappears, and representation of plurality opens up(92-93).

The camera captures the multi-layered incidents of the situation, it flows and circulates within the space as a flea between all the participants. The person holding the camera asks what is the meaning of this, of photo shooting; and his confusion can be seen through the inconsistent way of filming. This fact emphasizes a reality “inside the camera” that can be considered as a conceptualized space. It takes into account all the participants in the photographic act- the camera, the photographer, the photographed subject, and the spectator. All are drawn together into the representative whole where they encounter each other and engage in an arena of collectivity.

In the film we can also observe the power relations and how they are re-manifested as a direct reference to the camera and its presence which the sovereign forces of production try to precluded from that space. Holding it- is a right of demand; a right for negotiation. The insistent refusal to accept the disenfranchised status. Azouly sought to answer the question of how anyone, even an oppressed person, who addresses others through photographs can become engaged and even a citizen in the citizenry of photography. She claims: Anyone who addresses others through photographs or takes the position of a photograph’s addressee, even if she is a stateless person who has lost her “right to have rights,” as in Arendt’s formulation, is nevertheless a citizen –– a member in the citizenry of photography. The civil space of photography is open to her, as well Through photography the dispossessed demand a right to political speech and action and invite the spectators to reinstate with them the space. If we go back to Lefebvre, we can find similar a possibility of citizenship manifested as a right to recognize and master (individually and collectively) the conditions of existence. He considers this as a political act, as an alternative production in its place of residence. In an article published in 972magazine, 2013, The directors said: “There is no room for guilt, only taking responsibility when a Palestinian and an Israeli Jew set out to produce jointly a documentary about Israel’s occupation as seen through Palestinian eyes. The physical, The social and political challenge is enormous…I believe the film succeeds not only because it’s good, but because it shows the partnership between Jews and Palestinians”.

The film emphasises the ability to display the circulation of thoughts, spoken opinions and possible actions toward plotting out a different political sphere in which the plurality of speech, action and duration are actualized. Pluralism can also be understood through the spatial form of struggle which is a dialectical encounter between centrality and periphery, agriculture areas and urban locality, institutions and civilians, possessors and the dispossessed and Palestinians and Israeli directors working together.

If we are looking back at the discourse of photography since Ronald Barthes who defined photography as a myth and looked for the symbols of the post modern society, and following him Suzan Sontag, who issued photography as a moral problem of our time with a lack of empathy towards the weak, the object to be photographed. Those two important trajectories of looking at photography never really considered a reversed action of the object of pain taking the shot, when she is the one who is holding the camera. Nevertheless, we should draw out from the historical way of looking at photography as an enhanced social activity, to a new value of the social aspect as Azoulay analysis it, concerning the photographic action itself, the civil private participation. Meaning that, the photograph of politically induced suffering or pain creates a right and constitutes an emergency demand. “5 Broken cameras” enables a right, a right-as-mean for those who are struggling for their fundamental demands. The demand which is always at risk, in change, ‘under construction’, always in need of creative tensions, always producing inequalities and injustices at one end while striving to resolve them at the others.

List of References Azoulay Ariella. 2008. The Civil Contract of Photography: New York: Zone Books, 2012. Lefebvre, Henri. 1991.The production of space . Trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith. Oxford:Blackwell.Lefebvre, Henri, 2000. Lefebvre, Henri. 2003. The urban revolution. Translated by Robert Bononno. Minneapolis:University of Minnesota Press “Bili’in”, The Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem report, 2012.