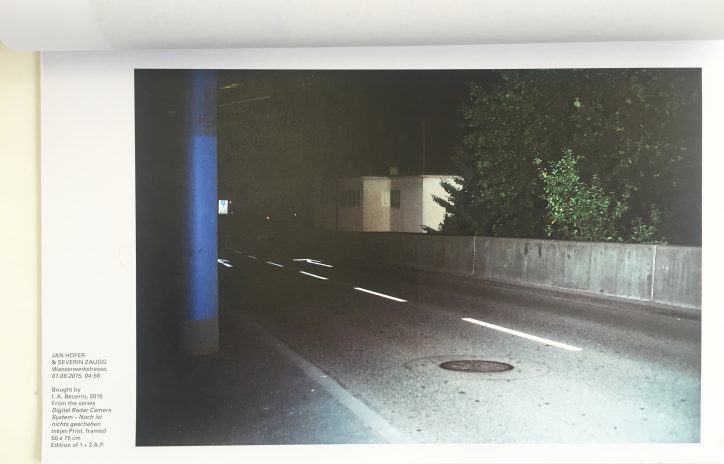

Si l’exposition Caméra(Auto)Contrôle prend acte d’un quart de siècle de politiques de vidéo-surveillance généralisée dans l’espace public, l’œuvre des deux jeunes artistes zurichois Jan Hofer & Severin Zaugg nous rappelle que c’est au début des années 60 que la police commence à utiliser les premiers radars, ou systèmes de caméra de surveillance routière. Si les photographies d’excès de vitesse montrant le visage et la plaque d’immatriculation du conducteur imprudent restent confidentielles, les artistes ont réussi à mettre la main sur les photographies représentant des sections de rues vides que les opérateurs photographes de la police zurichoise réalisent pour tester et garantir l’efficacité des appareils. Ces photographies semi-automatiques sont imprimées au fur et à mesure qu’un collectionneur achète une image. Il obtient alors le dernier cliché enregistré sur les serveurs de la police

English version bellow

Interview avec les 2 artistes réalisée pour la publication Digital Radar Camera System parue à l’occasion de leur exposition à l’Espace JB, Genève dans le cadre des 50JPG du 27.05 au 26.08.2016. Jan Hofer & Severin Zaugg font également partie de l’expositionCaméra(Auto)Contrôle

SL Sébastien Leseigneur

JH Jan Hofer

SZ Severin Zaugg

JH : Cet envoi fait partie intégrante de notre exposition « Digital Radar Camera System – Encore rien n’est arrivé » à l’Espace JB qui aura lieu pendant la triennale 50jpg à Genève. Nous voulons faire connaître notre travail et le rôle que le public y trouve.

SZ : C’est un travail photographique en continuelle évolution où nous transformons des images prises par la police dans le cadre de son activité en images à part entière.

JH : Elles sont tirées de contrôles de vitesse effectués par la police de Zürich à l’aide de radars mobiles. La police utilise un ensemble composé d’un radar, d’un flash, et d’un trépied qui est facilement transposable à différents lieux.

SZ : Avant de procéder au contrôle de vitesses, la police prend une image de référence de la scène sans voiture dans le champ de vision de la caméra. Nous travaillons à partir de ces images-là.

SL : Quel a été le déclencheur de ce travail ?

JH : Cela a commencé avec notre intérêt pour la photographie pragmatique. Nous étions à la recherche de quelqu’un qui pratique la photographie sans but esthétique.

SZ : C’est dans cette perspective que nous nous sommes tournés vers la police de Zürich et que nous avons découvert que ses agents étaient les auteurs de photographies de paysages vides très intéressantes.

JH : A partir de là nous avons développé un projet où nous transposons ces images dans un autre contexte et nous leur offrons une audience. La première étape a été de publier une série de ces photographies dans un livre d’artiste. Par la suite, nous nous sommes efforcés de détacher ce travail du support qu’est le livre pour les présenter en tant que tirages encadrés accrochés au mur.

SZ : Mais nous produisons uniquement un nouveau tirage quand un collectionneur vient vers nous avec l’intention de permettre de continuer le projet en achetant la dernière image prise…

JH: Le résultat est une série en évolution. L’exposition à l’Espace JB présentera l’état actuel du projet.

SL : Vous êtes sûrement familier du travail de l’artiste allemand Peter Piller qui a arrêté de prendre des photographies et qui présente des images tirées de journaux. Son livre Archive Peter Piller commence avec une image représentant un paysage vide accompagné de la légende : Il n’y a encore rien à voir : Sur la Boltzplatz à Süderwalsede doit se construire la maison du barbecue. Pouvez-vous me parler de la relation de ce travail avec le vôtre ? [ fig.2]

JH : Nous nous sommes confrontés au travail de Peter Piller depuis le début de notre projet en 2011. Notre professeur Kurt Eckert, nous en avait parlé à l’époque. Nous percevons clairement le rapport étroit avec son travail au point même de faire référence à son oeuvre en détournant son titre Noch ist nichts zu sehen (Encore rien n’est à voir) en Noch ist nichts geschehen (Encore rien n’est arrivé) que nous avons choisi comme sous-titre à notre exposition.

SL : Peter Piller travaillait dans un bureau qui gérait les archives d’images de presse. Au lieu de faire le travail pour lequel il était engagé, il produisait son propre travail. Il profitait du système en quelque sorte. Comme lui, vous avez développé une relation avec une entité extérieure, dans votre cas il s’agit de la police. Pouvez-vous m’en dire plus à leur sujet, comment ils travaillent et comment vous avez pu les approcher ?

JH : Nous les avons tout simplement appelés et ils nous ont invités à venir leur rendre visite. Ils nous ont présenté leur bureau et leur matériel et expliqué leur démarche photographique. C’est durant cette visite que nous avons soudainement vu ces images vides sur un écran.

SL : Mais vous étiez à la recherche de ces images vides ?

JH : Non, absolument pas. Nous ne savions même pas qu’elles existaient.

SL : Alors que cherchiez vous en y allant ?

JH : Nous voulions mieux comprendre leur démarche technique et pratique autour des radars mobiles. Nous étions intéressés par des images montrant des voitures en infraction de vitesse. Dès le début ils nous ont prévenus qu’ils ne pourraient jamais nous donner ces images-là étant donné que ce sont des images à charge, des pièces à convictions. Le problème ne se présentait pas avec les images de contrôle des rues vides.

SZ : Tout s’est naturellement mis en place. Premièrement, nous avions un intérêt pour le processus en lui-même, puis nous avons découvert ces images vides et au final nous avons pu développer notre travail autour de cela.

JH : Au début, nous n’étions pas sûrs de pouvoir convaincre la police d’adhérer à notre projet mais elle s’est montrée très ouverte à nos idées.

SL : Pouvez-vous m’en dire davantage de l’angle de la prise de vue? Je trouve la rigueur de l’orientation du cadrage très intéressante. Ces images sont construites avec beaucoup d’attention et l’on sent la présence d’un opérateur.

SZ : Lors d’une de nos visites, ils évaluaient les résultats d’un nouvel appareil qu’ils venaient de recevoir. Il y avait probablement quatre personnes autour de l’écran, analysant minutieusement les images, discutant leur précision, suggérant des variations minimes.

JH : Ils discutaient vraiment de photographie.

SZ : Mais clairement dans un but factuel. Il y a une rigidité et un déterminisme dans ces images qui provient du protocole technique nécessaire à ce genre d’images légalement valables.

JH : Ils ont choisi un angle spécifique qui répond aux besoins de voir la plaque d’immatriculation, la marque, le modèle de la voiture, et la personne conduisant le véhicule. Arriver à combiner ces paramètres est un exercice difficile qui demande une vraie technique photographique. [ fig.1]

SZ : Et en plus il faut tenir compte du fait que le système doit pouvoir fonctionner par tous les temps, de jour comme de nuit.

SL : Oui, beaucoup de paramètres qui finalement donnent naissance à une image très complexe. On a presque l’impression d’entrer dans un univers fantastique.

JH : Et je dirais que c’est un angle depuis lequel vous ne feriez jamais une photo si elle était basée sur des considérations esthétiques.

SL : Cela me fait penser à certaines images de Jeff Wall, vous savez, il y a cette série d’angles et de coins de rue. Parfois, cela m’évoque aussi ces images qui essayent de piéger les fantômes. [ fig.3, fig.4, fig.5]

SZ : Oui je vois ce que tu veux dire. Lorsque des gens voient des reflets créés par l’objectif et pensent qu’il s’agit de la présence d’un fantôme.

JH : En parlant de fantôme, je trouve que ces images de rues vides peuvent aussi avoir quelque chose d’étrange, qui fait peur. C’est comme s’il y avait quelque chose d’invisible qui rôde dans le coin. Et peut être qu’il y a vraiment quelque chose dans ces lieux, ce qui expliquerait pourquoi les gens ont tendance à y rouler trop vite.

SZ : Ce qui leur donne mauvaise réputation.

SL : Je vois également un lien avec le projet de l’appareil semi-automatique de Jules Spinatsch. Vous connaissez ses images panoramiques ?

JH : Celles du WEF à Davos ? [ fig.6]

SL : Oui, il a fait plusieurs séries à Davos, puis récemment dans une prison. Nous allons d’ailleurs en présenter une à l’occasion de l’exposition Caméra(auto)contrôle au Centre de la Photographie à Genève. J’aimerais aussi parler de la relation de la photographie au monde scientifique et l’utilisation de ce medium en tant que preuve. Nous savons que parfois cela mène à de la manipulation.

JH : Oui, cela me fait penser au livre Evidence de Larry Sultan et Mike Mandel que Severin et moi aimons beaucoup. C’est une collection d’images trouvées qui représentent la mise en place ou le résultat d’une expérience scientifique. A travers ce travail, Sultan et Mandel démontrent que ces archives ont une qualité photographique qui va bien au-delà de leur but premier.

[ fig.7]

SL : Au Centre de la Photographie c’est le sujet d’étude même de nos réflexions autour du medium. Nous prenons en compte tous les aspects de la production photographique humaine, aussi bien la photographie d’objets, que les archives photographiques, la photographie policière, la photographie scientifique… Mais qu’en est-il de la reproduction de ces images, de leur copyright. Vous rendez-vous compte que ces radars photographiques sont parmi les premières machines à produire des images automatiques contrôlées ? Que cette technologie est maintenant développée et mise en place dans l’espace public aux quatre coins du monde ? Depuis un quart de siècle, nous vivons dans un monde où il y a des caméras quasiment partout. Cependant, il y a quelque chose de particulier dans ces images, car liées à un événement. Avez-vous parlé du copyright avec la police ?

SZ : Nous estimons que la notion du copyright n’est pas entièrement résolue. Il y a bien sûr des règles qui définissent le droit du citoyen. Nous ne savons pas ce que la police devrait fournir comme information, si une personne les lui demandait. Mais les policiers avec qui nous travaillons sont d’accord que nous fassions des reproductions de ces images.

JH : Dans ce cas précis, la définition de l’auteur est ardue, car c’est une machine qui réalise automatiquement la prise de vue. Les policiers mettent en place l’appareil en suivant un protocole élaboré par une tierce personne. Le lieu et l’heure sont déterminés en fonction des tendances spatiales et temporelles des violations. Finalement, nous reprenons ces images et les mettons

dans un nouveau contexte leur donnant ainsi une nouvelle intention. Cette conjonction de différents aspects rend la définition de l’auteur difficile.

SL : Imaginons qu’une personne ait reçue ce mailing et lise notre discussion. En regardant les images, elle décide d’aller de l’avant et de participer au projet, que se passe-t-il ensuite ?

SZ : Si cette personne nous approche alors nous nous mettrons en contact avec la police qui nous livrera la photo la plus récente. Nous la lui présenterons, puis nous procéderons à la reproduction de cette image en tant que tirage unique et officiel.

JH : Donc chaque achat déclenche le processus d’acquisition du serveur de la police afin de devenir une image de paysage urbain à part entière.

SZ : L’acheteur est le déclencheur de la création de l’oeuvre.

SL : …comme un autre aspect de ce processus automatisé.

JH : Exactement. Tout comme la photographie de police, une bonne partie de notre travail est définie par l’action de l’autre. Nous générons un système où l’interaction crée le produit final.

SL : Avez-vous déjà réfléchi à la durée de ce projet ?

JH : C’est un aspect intéressant. Je ne sais pas… J’imagine que ce travail pourrait exister aussi longtemps que la police continue de prendre ce genre de clichés. Tant qu’ils photographient, il y a la possibilité que des gens viennent vers nous et que nous continuions à réaliser la suite de cette série le restant de nos jours. Si des gens sont intéressés… Le jour où nous aurons disparu… ça c’est une autre question…

SL : Peut être que quelqu’un d’autre continuera le projet.

JH : Oui peut être…

SL : C’est un projet ouvert ?

JH : Peut être que c’est plus de l’ordre d’une start up. Ou comme le cas de Franz West Furniture, dont les meubles sont encore produits après sa mort par les gens de son studio.[ fig.8]

SZ : Il est possible que les paramètres et la technologie que la police utilise changent aussi radicalement. Il y a un danger inhérent au projet lui-même. Aujourd’hui, ils travaillent déjà avec un appareil différent de celui d’il y a cinq ans. Beaucoup de polices avec qui nous nous sommes récemment entretenus sont passés du film noir blanc (analogique) à la prise de vue digitale. Personne ne peut prédire combien de temps il vont continuer à travailler avec cet équipement.

SL : Cela évolue en fonction des progrès technologiques.

SZ : Exactement. Ils développent et expérimentent différents systèmes. Il y a une industrie qui est derrière tout ça. Mais avant tout, nous dépendons du bon vouloir de la police de continuer à nous fournir des images. En fait, nous venons de commencer l’exposition de ce travail, nous n’avons donc pas encore vraiment songé à sa fin…

JH : C’est juste le début. Encore rien n’est arrivé.

Jan Hofer & Severin Zaugg (tous deux nés en 1988) ont étudié ensemble à la ZHdK (Haute Ecole des Arts de Zürich) de 2009 à 2013. Hormis Digital Radar Camera System, ils ont collaboré sur différents projets. Ils vivent et travaillent respectivement à Zürich et Stuttgart.

***

While the exhibition Caméra(Auto)Contrôle takes note of a quarter century of policies regarding the spread of security videos throughout public space, the work of the pair of Zurich artists Jan Hofer & Severin Zaugg is here to remind us that it was in the early 1960s that the police began using the first radars and camera systems for monitoring roads. While photographs of speeding violations showing the face and license plate of the reckless driver remain confidential, the artists have managed to obtain photographs depicting empty roads, which the Zurich police unit in charge of the automatic cameras shoots to test and guarantee the effectiveness of the devices. These semi-automatic photos are printed out whenever a collector buys an image. He or she obtains the latest picture recorded on the police servers.

This Interview with the artistes is published in Digital Radar Camera System, an edition printed for their solo exhibition at the Espace JB, Genève, as part of 50JPG from 27.05 to 26.08.2016. Jan Hofer & Severin Zaugg are also part of the exhibition Caméra(Auto)Contrôle:

SL: Ok, first of all, why do you do this mailing and what is its function in your work?

JH: Well, making this mailing is part of our show ‘Digital Radar Camera System – Nothing has happened yet’ at Espace JB, during the photo triennal 50jpg in Geneva. With it we want to let people know about our work and their role in it.

SZ: It’s a photographic work in progress where we transfer functional byproducts of police photography into photographs in their own right.

JH: The pictures come from mobile speed controls carried out by the Zurich traffic police. They work with a compact set of radar, camera, flash and a tripod which they can easily set up in different locations.

SZ: Just before they start capturing speed violations, they take a control picture of the empty street, no car in it, just the bare location. And those are the images we are working with.

SL: Ok, but how did all that come along?

JH: It started with our interest in pragmatic photography. We were searching for someone who did serious photography without pursuing any aesthetic goals.

SZ: In this context we reached out to the traffic police of Zurich and found out that they were generating these very interesting images of empty landscapes.

JH: And from there we developed a project in which we bring these pictures into an other context and give them an audience. The first thing we did was publishing a series of these images in an artists book. Later we detached the work from the book as a medium and started an serial work with the images in framed prints.

SZ: But, we work under a condition. We only ever produce new prints when someone reaches out to us and is interested in continuing the project by buying the newest part of it…

JH: This results in an ongoing photographic series and in our show at Espace JB we are going to present the current state of it.

SL: I guess you know the German artist Peter Piller who stopped making photographs and started to present images from the newspapers. His book ’Archive Peter Piller‘ starts with one photograph of an empty landscape with the caption: Noch ist nichts zu sehen: Auf dem Bolzplatz in Süderwalsede soll das Grillhaus entstehen. Can you tell me something about your relation to this work? [ fig.2]

JH: Well Peter Piller was present from pretty much the beginning of our project in 2011. Our teacher at the time, Kurt Eckert, told us about him. We of course see the relation and also refer to Pillers work in the subtitle of our series. There we paraphrased his title ‹Noch ist nichts zu sehen› (Nothing yet to be seen) with ‹Noch ist nichts geschehen› (Nothing has happened yet).

SL: Peter Piller was working in an office of an archive of press images and during the time he was supposed to work, he was doing his own work. He was messing with the administration a little bit. Like him you seem to develop a relation to an administration, in your case the police. Can you tell me a little more about the police, how they are, how they work and how you approached them?

JH: We gave them a call and they invited us and gave us a tour through their offices and explained their whole work process. It was during that tour where we suddenly saw these empty images on a screen.

SL: But you knew you were looking for those empty pictures?

JH: No. We didn’t even know they existed.

SL: Well, what were you looking for at the time?

JH: We were just trying to find out more about their photographic practice with the radar cameras. So we were interested in the pictures that show cars going too fast. But the first thing the police said, was that they could never give us any of theses images since they are pieces of evidence. This problem did not exist with the images of empty streets.

SZ: Things just came together. First we had this interest in the matter itself, discovered the empty pictures and in the end developed a work around them.

JH: At times we were not sure if we would succeed to convince the police of our project, but they were very open to our ideas.

SL: Can we speak a bit more about the orientation of the camera? That’s something very interesting. This very rigorous way the frame is orientated. Those pictures are constructed with a lot of attention and we feel the presence of an operateur.

SZ: When we went there once, they were checking the first results of a new camera. There were maybe four people around the screen, attentively analyzing the pictures, checking their accuracy, suggesting fine changes to the set up.

JH: They were really discussing photography.

SZ: But of course with their completely fact driven purpose, so there is this decisiveness and rigidness in these pictures. This comes from all the rules and the pragmatism of their practice. Which is necessary to take a legally valid photo.

JH: They chose a very specific angle because they need to see the front license plate, the model of the car and the person driving. All of this results in a big challenge for the whole photographic equipment and it’s settings.

[ fig.1]

SZ: On top of that, it has to work in any weather and at any time of the day.

SL: Yeah it’s a lot of parameters which finally result in a very complex image. At the same time it’s almost drifting into a fantastic atmosphere.

JH: And I think it’s an angle you would never end up shooting from, if you would take a picture based on aesthetic decisions.

SL: It reminds me of some Jeff Wall photographs, you know, there is this series of angles and street corners. But also sometimes it reminds me of these photographs that try to catch ghosts. [ fig.3, fig.4, fig.5]

SZ: Ah I know what you mean, when people see reflections on the lens and think that there are ghosts present.

JH: Talking of ghosts, I think that our images of these empty streets also have a scary or haunted notion. It almost feels like there is something slumbering in this area. And maybe there really is something about those places, because for some reason, people tend to go to fast there.

SZ: Which makes them notoriously dangerous locations in that way.

SL: I see a relation with the Jules Spinatsch’s project of the semi automatic camera. I don’t know if you know those panoramic pictures.

JH: Ah, the ones from the WEF in Davos? [ fig.6]

SL: Yeah he did a lot of them. He did some in Davos. He also recently did a series in a prison and we’re going to present one in the show Caméra(auto)contrôle at Centre de la photographie in Geneva. I also wanted to talk about the relation between photography and the world of science where photography in the beginning was used to prove things. And we know that it sometimes leads to manipulation.

JH: This reminds me of the book Evidence by Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel, which we both like a lot. It’s a collection of found photographs displaying the setting or the outcome of scientific tests. With their work Sultan and Mandel show that this archive material has a photographic quality that goes way beyond its original purpose of simply being a piece of evidence.

[ fig.7]

SL: Here we are totally in the field of the visual studies and this is very much our concern at the Centre de la photographie. In our reflection on photography we consider all human visual production also the product photography, the archive photography, police photography and scientific photography… But what about the reproduction, the copyrights of this automated photography. Do you realize that these machines were almost the first machines to produce automatic control photography and this technology is now developed everywhere in the world, in the public space. We live in an era, since almost a quarter century, where we have cameras everywhere. Still I see something special with these images because there is a relation to an event. Did you talk about copyrights with the police?

SZ: We assume that the copyright situation is not a hundred percent clear. There may be a regulation on what a governmental institution owes to the public and so on. We don’t know exactly how much they would have to disclose if someone requested that. As of now, the officers we’re working with are fine with our reproductions.

JH: What remains tricky is the question of authorship. Because first of all there is this machine that automatically takes pictures. Then there are the police officers who set up the machine. But then again they are following a strict manual written by someone else. Time and location again are chosen based on the general traffic violation tendencies. And on top of all that, we take these pictures into a new context, attributing new meaning to them. So the authorship remains very blurry.

SL: So what if somebody has gotten this mailing, the person is reading our words, looking at the images and then decides that he or she would like to have one of these pictures as well. What happens next?

SZ: So if someone approaches us, we will contact the police and get the most recent photo of an empty street from their server. After that we suggest the picture to its potential buyer and then, as a final step go on to produce it as a unique authorized print.

JH: So each purchase initiates that a picture is taken from the police servers to become a landscape or cityscape photography in it’s own right.

SZ: The buyer not only owns the piece but initiates it first.

SL: This looks like another part of the automatic process.

JH: Exactly. Similar to the police photography, a big part of our work is defined by other people. We generate a system where others cause the final outcome.

SL: Have you ever talked about how long you could do this work?

JH: Well that’s an interesting point. I don’t know… I guess the work could go on as long as the police is doing their photographic work. As long as they are taking these pictures there is the potential that people are coming to us and that we realize new parts of the series for our entire life… If people are interested… And then once we die… That’s another question…

SL: Maybe somebody else will continue the project.

JH: Yeah maybe.

SL: It’s an open source project?

JH: Maybe it’s more like a start-up or I don’t know. Maybe a bit like Franz West Furniture that is still being produced after his death by the people of his studio.

[ fig.8]

SZ: Also the set up the police operates with is subject to change. So there is a natural danger to the project. Currently they photograph with a different camera than they did 5 years ago. Many police forces we talked to, had recently changed from black and white film to digital photography. And who knows how long they will continue to operate with that exact camera.

SL: It follows technical evolution.

SZ: Right. And they are trying different things. There is certainly an industry behind these systems. And most of all we depend on the goodwill of the police to still provide us with pictures. Also since this new part of the work started relatively recently, we did not really think about the termination of it yet.

JH: This is just the beginning. Noch ist nichts geschehen.

Jan Hofer & Severin Zuagg (both born in 1988) studied together at ZHdK between 2009

and 2013. Besides Digital Radar Camera System they realized various collaborative projects. Currently they live and work in Zurich and Stuttgart.